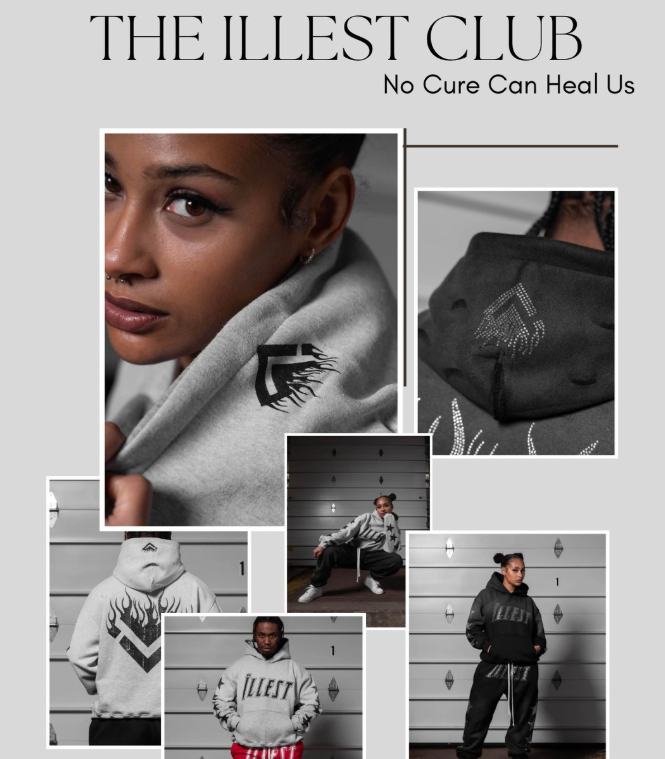

The Illest Club Turns Community Into Currency At New York Fashion Week

By PAGE Editor

In an era when streetwear brands are chasing algorithms, drops and dopamine, The Illest Club is chasing something older — and arguably more durable: community.

During New York Fashion Week, while legacy houses staged tightly controlled runway narratives downtown, Gavin “WhyNotGav” Pennington opted for something more kinetic. His brand’s “Virus Response Unit” — a fully wrapped hazmat-style truck stamped with the slogan “No cure can heal us” — cut through Manhattan for three secret, rapid-fire drops before culminating in an invite-only gathering on Hester Street in the Lower East Side.

For Pennington, spectacle is not a marketing tactic. It’s a delivery system.

“Valentine’s Day is usually hearts and Hallmark,” he told me inside the red-lit VIP section of his Hester Street pop-up. “We’re doing a controlled release. If you find us, you’re in. If you miss it, that’s the point—desire is the virus, and we’re not selling the cure.”

Scarcity As Signal, Community As Infrastructure

The Illest Club describes itself as a “culture-first streetwear house built on mythology, scarcity and spectacle.” But beneath the hazmat graphics and outbreak language is a more strategic through line: engineered intimacy.

Over the course of a single afternoon, the Virus Response Unit hit Times Square, Washington Square Park and Mulberry Street, throwing free product into crowds that had decoded coordinates through the brand’s social platforms and private lists. Each stop lasted roughly 10 to 15 minutes — just long enough to feel urgent, not long enough to feel transactional.

“Product distribution is intentionally limited and packaged like evidence — not merch — to keep the moment tight, rare and filmable,” Pennington explained.

That language matters. In a saturated market, product is abundant. Proof of belonging is not.

“I feel like a lot of brands nowadays… it might be called something, or it might be so focused on the clothes, but there’s no community feel,” he said. “I feel like community is what makes the brand. Your clothes can be so good, your marketing can be so good, your photo shoot can be so good — but if there’s no community around your brand, it’s not really anything.”

This is the core inversion at the heart of The Illest Club: the clothing is the artifact. The community is the infrastructure.

From Phone Designs To Fashion Week

Pennington’s ascent is inseparable from the digital-native culture he emerged from. A Philadelphia-based founder who started the brand at sixteen, he designed early pieces on his phone, organized shoots with his brother and friends, and leveraged the same platforms that shaped his taste.

“I’m a YouTube kid,” he said. “I watched YouTube, influencers, rappers. I used to just watch music videos when I used to design, just looking at the lifestyle and be like: I wanna be like that.”

That aspiration — not simply to sell clothes but to construct a world — now defines the brand’s expansion strategy. DC. New Jersey. Now Manhattan during Fashion Week. Each pop-up scales in ambition, but not in distance from its base.

“This is our third pop-up,” he said. “First pop-up was in DC, second pop-up was in New Jersey, third pop-up, New York City, Fashion Week, of course. I just wanted to really come here, put my foot down to show, like, I’m here to stay.”

Inside Mi Casa Studios, the activation blurred installation and house party. Red lighting washed over walls layered in Illest graphics. Artist Temsley painted live. A back VIP section hosted food and drinks. Outside, the hazmat truck functioned as both stage prop and signal flare.

The aesthetics are theatrical. The subtext is ownership.

“I want to make just a world around my brand,” Pennington said. “Away from clothes. That’s the biggest thing I do — from just the graphics that you can really… like, you can look at it and feel the vibe of the brand.”

Streetwear As Mutual Exchange

Streetwear’s most enduring brands — from Supreme’s early Lafayette Street era to today’s community-first labels — understood something traditional luxury often overlooked: loyalty compounds when participation feels reciprocal.

Pennington leans into that reciprocity. The free product tosses weren’t random generosity; they were reinforcement.

“The biggest thing is giving back to the people that support me — the kids and people my age that really just see me and get inspired by what I do,” he said. “Those are the people that gonna really go hard for you.”

In other words, community is not audience. It is co-creator.

For a young Black founder navigating both aspiration and scrutiny, the brand doubles as self-expression and shield.

“The biggest thing that inspired me was just everything I went through in my life,” he said. “From playing sports, going through failures, disappointments, to just life in general, being a young Black man. So I just put it all into one — what I feel comfortable in, what I think is cool.”

That authenticity — unsanitized and sometimes intentionally opaque — is part of the allure. Pennington is reluctant to over-explain his moves.

“I’m really closed off, too,” he admitted. “I don’t really like saying what I’m doing… Just like, if you know, you know.”

The Feedback Loop

Streetwear brands often claim to be “for the culture.” Few are structurally built by it in real time.

The Illest Club’s Virus Drop model creates a feedback loop: the brand fuels urgency; the community amplifies it; the mythology deepens; the next drop becomes inevitable. By the time the Valentine’s Day collection went live online, the physical activation had already seeded narrative capital across TikTok, Instagram and group chats.

Pennington understands that today’s consumer doesn’t just want a garment. They want proximity to a lifestyle.

“I wanna feel like a rapper, I wanna feel like I’m a movie star, I wanna feel like I’m an influencer or a streamer,” he said. “That’s how I wanna feel with the brand, and I feel like that’s what kids gravitate towards. They gravitate toward a lifestyle of something they wanna be.”

The question for emerging streetwear brands is no longer whether community matters. It is whether the brand is willing to architect itself around that community — even when it requires relinquishing control.

As the hazmat truck rolled through Manhattan, what The Illest Club staged was less an outbreak than an experiment: what happens when a brand treats its supporters not as customers, but as insiders?

In Pennington’s universe, the answer is simple.

“If you find us, you’re in,” he said.

And in streetwear, being “in” has always been the real product.

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT FASHION?

COMMENT OR TAKE OUR PAGE READER SURVEY

Featured

Libertine’s Fall/Winter 2026 collection transforms the grandeur and architectural precision of Sanssouci Palace into a richly embroidered, intellectually infused wardrobe that marries historical opulence with Hartig’s signature storytelling.