Fur Isn’t Back—It’s Breaking Down: Inside an industry in terminal decline

By PAGE Editor

For months, fashion headlines flirted with a familiar provocation: fur is back. The narrative gained traction through celebrity sightings, runway ambiguity, and the growing difficulty—intentional or not—of distinguishing real fur from synthetic or bio-based alternatives. But beneath the noise, the data tells a far less glamorous story. The global fur trade is not resurging; it is unraveling. Shrinking production, sweeping legislation, collapsing public support, and a decisive shift within fashion media suggest that 2026 may mark a point of no return.

A collapsing supply chain

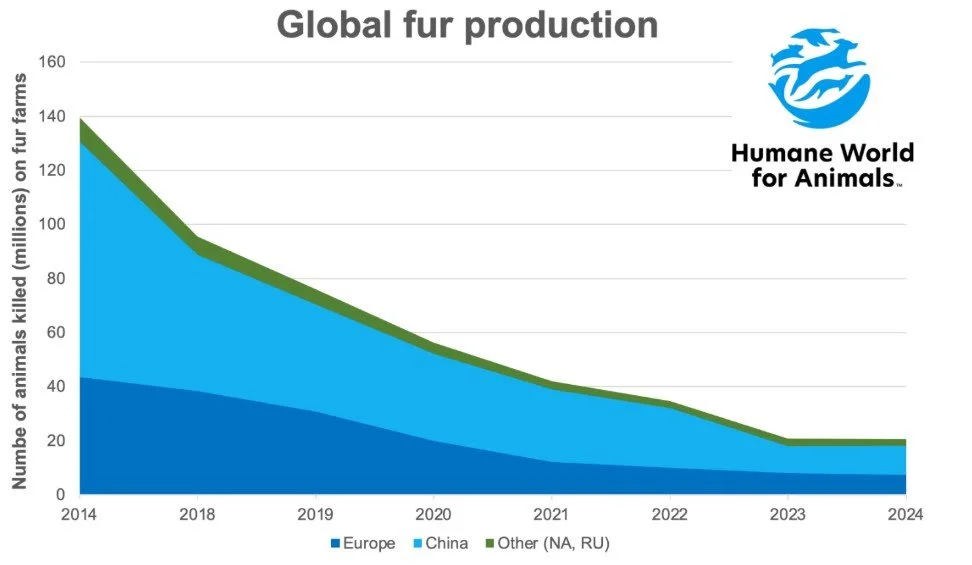

The most telling indicator of the industry’s condition is production itself. Over the past decade, the number of animals killed annually for fur has fallen by approximately 85%, dropping from an estimated 140 million in 2014 to just 20 million in 2024. This is not a cyclical dip—it is a structural collapse driven by economics, ethics, and regulation.

Once a cornerstone of luxury exports in parts of Europe, fur farming has become financially untenable. Public subsidies, rising biosecurity risks, and mounting compliance costs have hollowed out the sector. In Europe alone, the industry now carries an estimated €446 million in annual public costs, a figure that has intensified political scrutiny rather than securing sympathy.

Europe turns its back on fur

Legislation has accelerated the industry’s decline. In December 2025, Poland—previously responsible for nearly half of the European Union’s fur production—voted to ban fur farming, with a phase-out period extending to 2033. The decision sent shockwaves through the sector, positioning Poland as the 18th EU member state and 24th country worldwide to enact such a ban, following Romania (2024) and Lithuania (2023).

Earlier precedents tell a similar story. The Netherlands, once the EU’s second-largest mink producer, fast-tracked its shutdown from 2024 to 2021 after COVID-19 outbreaks ravaged mink farms. Norway, formerly the world’s largest fox fur producer, voted to end fur farming entirely after widespread welfare violations came to light. France, Ireland, Italy, Belgium, Austria, and the United Kingdom have all followed suit, either through outright bans or regulations so strict that farming became economically impossible.

Looking ahead, an EU Commission decision expected in March 2026 could effectively seal the fate of the remaining European fur industry. With a 2027 ban on American mink breeding already looming and growing concern over public health and invasive species, the regulatory walls are closing in from every direction.

Import and sales bans tighten demand

Production bans are only half the story. Demand is also being legislated out of existence. Switzerland passed a fur import ban last year, and further restrictions are under discussion. In the United States, cities including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Berkeley, and West Hollywood have banned new fur sales, paving the way for California to become the world’s first fur-free state in 2019. Additional municipalities across Massachusetts, Michigan, and Florida have since followed.

Globally, Israel set a historic precedent in 2021 by becoming the first country to prohibit the sale of fur altogether. Each of these measures chips away at the remaining market, making fur farming increasingly unprofitable and leaving little room for recovery.

Fashion walks away

Perhaps the most decisive blow has come from fashion itself. As designers, institutions, and media reassess their responsibilities, fur has lost not only market share but cultural legitimacy.

The Council of Fashion Designers of America has ended fur promotion at New York Fashion Week. In October, Condé Nast announced a fur-free editorial policy, and in December, Hearst Magazines International confirmed it would eliminate all promotion of animal fur across its global platforms. These are not symbolic gestures; they represent a withdrawal of visibility, aspiration, and endorsement from the industry’s most powerful tastemakers.

At the same time, innovation has shifted toward animal-free and plastic-free alternatives, reframing luxury around material intelligence rather than extraction. In this context, fur reads less like heritage and more like obsolescence.

Ethics, exposure, and public memory

The industry’s reputational decline has been reinforced by public reckonings. This year marks one year since Humane World for Animals rescued hundreds of animals from a fur and urine farm in Ohio. The operation exposed a little-seen corner of the trade, where animals were bred simultaneously for fur, for sale as exotic pets, and for urine harvesting. Following the rescue, the animals were placed with sanctuaries and rehabilitation centers across the U.S., including Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation, Inc., where dozens are now thriving.

These moments matter. They humanize—or perhaps more accurately, animalize—an industry that has long relied on abstraction and distance to survive.

The end of the illusion

Taken together, the picture is unmistakable. Fur is not experiencing a renaissance; it is enduring a prolonged and increasingly visible collapse. Markets are disappearing. Governments are withdrawing support. Fashion has moved on. Consumers are unconvinced.

What remains is an industry clawing for relevance in a world that has already begun to legislate, innovate, and imagine beyond it. The future of fashion is being built without fur—and increasingly, without the illusion that it ever truly left.

For further insight or expert commentary on the global fur trade and its decline, contact Humane World for Animals.

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT FASHION?

COMMENT OR TAKE OUR PAGE READER SURVEY

Featured

An immersive digital debut introduces four signature collections rooted in natural architecture, symbolism, and hand-engraved craft.